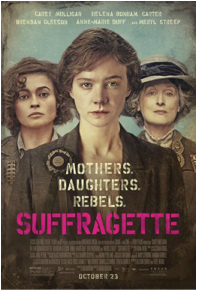

Middle-aged Novelist Joins Political Party: it’s not much of a headline but as an inveterate political fence-sitter and someone who has never felt a particular affinity with the Westminster suits, whatever the hue, it feels like a big deal to me. The party I've joined is the newly minted Women’s Equality Party and the reason: I agree with them. Perhaps it’s the same trait that’s made it difficult for me to adhere to a particular cause that also makes me able to construct characters in my fiction: the desire scrutinise things from multiple perspectives. But when it comes to women and equality I struggle to find, let alone empathise with, a counter argument. Who could deny that whatever the gender, a person doing a job should be paid the same as another person doing the same job, irrespective of the shape of their dangly bits? The women I write about all lived in a world in which inequality went unquestioned. It wasn't until a little more than a century ago that the suffragette movement was, alongside its Votes for Women campaign, battling to open a political discourse about gender equality, as Sarah Gavron’s recent film Suffragette powerfully demonstrates. But the film also exposes the fact that we still have a long way to go and it is this that the WEP intends to address.  What the film does is create a fictional character at its heart, a working class woman, who becomes the lens through which to tell the story of a movement that has become in many minds associated with the privileged classes. Think of Mrs Banks in Mary Poppins, be-sashed and blithely warbling Sister Suffragette in suburban Cherry Tree Lane. This retelling allows us to understand the brutality of women’s lives and the struggle to be heard. One critic lamented the fact that an invented character was placed at the heart of true events, claiming it weakened the message. I disagree; it is exactly the story of that forgotten woman, speaking for all women of her class, that invests the film with its substantial force. Women’s stories matter; particularly those that have been swept under the carpet of history. It is a cause close to my heart, as my work as a writer is spent excavating such stories. But there seems to be an unconscious societal urge to ignore them or deem them less important than those of men. We have long been aware of a dearth of good roles for women in Hollywood and this spills over into publishing too. Over the last few years Vida statistics have highlighted the imbalance of female authors being reviewed in the serious press. This opened much needed discussion about women writers being given equality in the world of book prizes and led to a call by novelist Karmila Shamsie for a year of publishing only women. This is a worthy endeavour but there is something more subtle at play, which was exposed by Nicola Griffith’s recent data study in which she looked not at the gender of authors winning prizes but the gender of the protagonists in prize winning novels. The results were staggering in that overwhelmingly, the central characters in the winning books were male – even when authors were female: Mantel’s Cromwell novels are a good example of this.  What filled me with dismay was that even in the light of this, the shortlist of the latest MAN Booker Prize seemed like celebration of men. Of the six, all but one novel (Anne Tyler’s A Spool of Blue Thread) chosen by judges of both genders, were stories about men or groups of men. It seems from this that we (both men and women) find narratives about men more serious, more worthy of accolades, than those about women. There is perhaps a tendency to dismiss female focussed literature as romance, rather than idea, driven. Before I’m accused of having a case of sour grapes, I feel that I should state that I want, as much as the next person, the very best books to win awards. But the 2015 booker shortlist poses the question, was there really only a single remarkable book with a female protagonist published in the whole English speaking world this year? Looking back to the nineteenth century, there is an embarrassment of novels about women and often written by men: Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Madame Bovary, Anna Karenina and so on. But the unifying factor of all those works was that they carried a strong moral message for their readers: women who step out of line (particularly sexually) will get what’s coming to them. Thankfully the novel doesn’t exist so obviously as a moral corrective for society any more but just because it is no longer appropriate to force feed moral messages through the prism of literature, doesn’t mean that women’s stories should vanish altogether from serious fiction.  For millennia we have built our societies on stories, with far reaching effects. Think of the enduring messages from Greek tragedy and epic that continue to resonate in contemporary psychological theory. Fiction holds up a mirror to society but it is also asks questions about what it is to be human and sets patterns by which we find ourselves living. In privileging male stories, albeit unconsciously, we are building a society that automatically puts men on top. But by undermining women in this subtle way we are denying ourselves the potential for a rich and diverse culture. I believe that change occurs only when attitudes shift and it is just such an attitude shift that the WEP aim to instigate in with their policies. By aiming for, amongst other policies, gender balance in parliament, equal opportunities for girls in education, equal treatment of women in the media and an end to violence against women, then perhaps we can begin to explore new narratives with women at their heart on which to build a richer society. Women’s Equality Party: https://womensequality.org.uk

Nicola Griffith’s Data study: http://nicolagriffith.com/2015/05/26/books-about-women-tend-not-to-win-awards/ For more about Elizabeth Fremantle's novels search the site Elizabethfremantle.com

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Subscribe to Elizabeth's quarterly newsletter below:Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed