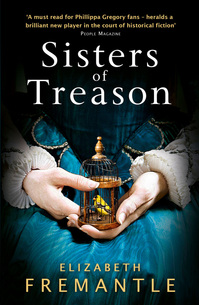

The mid-sixteenth century saw the rise of a new art form: the portrait miniature. Designed to be hidden, rather than displayed in public, miniatures were worn on ribbons tucked away from prying eyes amongst layers of clothing, in pockets and pouches, or in boxes – like Elizabeth I's collection of tiny likenesses. They often signified love and were exchanged as betrothal gifts, keepsakes or between clandestine lovers, but were also worn as covert symbols of political affiliation. It is one such portrait, an image of a woman, who many championed as Elizabeth I's successor, with her son, potentially a future King of England, that is a central symbol in my novel Sisters of Treason.  Lady Katherine Grey and her son Lady Katherine Grey and her son This portrait of Lady Katherine Grey and her son Lord Beauchamp is the first known English secular image of a mother and child. It is also, if you look very closely at the object Katherine wears round her neck, the first instance in painting of a miniature being worn. It is her husband's likeness and so this forms a kind of family group. When this was painted Katherine was imprisoned in the Tower of London for her unsanctioned marriage to Edward Seymour – indeed that is where she gave birth to little Lord Beauchamp.  Lady Katherine Grey Lady Katherine Grey The artist was Levina Teerlinc, the daughter of an illuminator of some renown, who came to England from Bruges, joining the household of Katherine Parr when she was queen. Teerlinc was remarkable as a sixteenth century woman earning her living as a painter, but more so in that she served as a court artist to four Tudor monarchs: Henry; Edward VI; Mary I and Elizabeth I, and would have worked on designs for jewellery, seals and documents as well as portraits. It is a great shame that more of her work has not survived but from the few images we have it is clear that she was instrumental in the spread in popularity of the limning or miniature. Specialist in portraiture of the period, Susan E James, makes a strong argument that Teerlinc was the author of A Very Proper Treatise Wherein is Briefly Set for the Arte in Limning that demonstrated the main tenets of the form. James is also of the mind, as is art historian Roy Strong, that Teerlinc may have taught Nicholas Hilliard who was to become one of the world's greatest practitioners of the art.  Perhaps Lady Jane Grey Perhaps Lady Jane Grey Teerlinc painted a number of images of the Grey family: the portrait of Lady Katherine with her son and another of her as a girl and also a much disputed miniature by Teerlinc that some, including David Starkey, believe to be a likeness of Katherine's older sister, the tragic Lady Jane Grey. This is hotly disputed and there is no definite image of Jane Grey but there is in these little portraits a clear suggestion of a relationship between Teerlinc and the Grey family. I have built on this in my novel, weaving the painter's life with that of the two younger Grey sisters Katherine and Mary, two girls whose lives were played out at the heart of the struggle for the Tudor succession, only to be forgotten when their Stuart cousins came to power. This brings me back to the portrait of Katherine and her son and the political significance of such an image. It was widely copied (I know of at least three similar images in existence) and would have been a covert demonstration of allegiance to the Greys and their claim to the throne. Elizabeth I, ever fearful of usurpers, had Lord Beauchamp deemed illegitimate and Katherine was to end her days in incarceration, but thanks to the intimate art of Levina Teerlinc we have an insight into a forgotten fragment of history.

Ref: Susan E James The Feminine Dynamic in English Art 1485-1603, Ashgate. Sisters of Treason –out 22nd May – is available for pre-order on Amazon.co.uk

2 Comments

|

Subscribe to Elizabeth's quarterly newsletter below:Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed