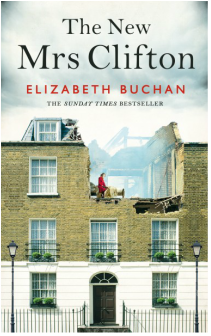

Elizabeth Buchan’s latest novel, The New Mrs Clifton, depicts London in 1945 in the aftermath of war. The fractured city, its buildings blasted open, symbolises the psychological scarring and fragmentation of her characters. Everyone is in some way bereaved and seeking something, anything, to dampen the pain. But when Gus Clifton returns from Berlin to the family house with a German bride on his arm his sisters, the widowed Julia and the wild Tilly, must hide their shock and hostility. Unbeknownst to Gus’s new bride he had left for the war engaged to his childhood sweetheart, the beautiful, loyal Nella and this betrayal is the catalyst for the two families, once happily interwoven, to unravel painfully with devastating effects. It soon becomes clear that the German Krista, with her skeletal body and haunted looks, who flinches when touched, is more damaged by far than any of the women she encounters in London. But the enmity she faces in London is nothing compared to her experiences in Berlin at the hands of the Russian occupiers. Though we soon learn that extreme hardship and the brutality she has encountered have made her stronger than she appears and she has many secrets, which are slowly revealed as the narrative progresses. The novel is shot through with mystery: why did Gus marry his strange, cold wife who is neither pregnant, nor apparently in love with him; what happened in Berlin; and who was the woman discovered thirty years later enmeshed within the roots of a large sycamore tree in the adjacent garden? The latter hangs darkly over the narrative like the tolling of a death knell. The writing is beautifully fluent, moving from scene to scene, peeling away the layers of English formality in a way that demonstrates a deft and invisible authorial control. Buchan has a gift for understanding the complexity and ambiguity of human emotions and also for creating a quiet and sinister tension, which gives the sense, as the narrative passes through the heads of its damaged characters, that everything is slipping inevitably towards catastrophe. The New Mrs Clifton is a captivating and gripping read that seduces utterly, until its final page, leaving a deep imprint on the imagination long after. The New Mrs Clifton is published in hardback by Michael Joseph. INTERVIEW WITH ELIZABETH BUCHAN EF: There is a very strong sense of place in the novel. Did you have a particular house in mind when you were writing and is there a significance to the part of London in which it is set? EB: I have been lucky enough to have brought up my family near Clapham Common and I love it – particularly in the summer when everyone surges onto it to picnic, play games, lunge the children and exercise. The Common has a long and honourable history, not least as a centre for William Wilberforce and the Clapham Sect while they fighting to abolish slavery – so it has a whiff of dissent about it. While researching The New Mrs Clifton, I got hold of the bomb maps published by the GLC which, area by area, showed the individual houses and buildings that had been damaged during the war and how badly. Since I walk past some of those sites every day, I was able to imagine the houses as they might have been without too much difficulty. EF: One of the great strengths of your writing is in articulating complex family relationships. In both I Can’t Begin to Tell You and The New Mrs Clifton you have created central female characters who are outsiders. What is it about the outsider that most interests you? EB: As an eight-year-old, I was sent off to boarding school because my parents had been posted abroad. I did not see them, or my two sisters, for a year. We took a bit of getting to know each other again when we did meet! I hasten to say that my parents were very loving ones and I was not the only child in that position but I have never forgotten the bewilderment and the loneliness which I felt and I know I call on that profound conviction of being an exile and apart when I am writing. How a man or a woman, or a child, negotiates their way out of their perceived isolation fascinates me because I remember it so well but, each time I write about it, I find a different aspect to it. For obvious reasons, war offers a very good theatre in which to fictionalize situations where a character is one side of the fence or the other. EF: One of the messages of the novel is that war creates complicated moral situations that defy straightforward moral explanations. Can you explain how you confronted some of the darker elements of your story? EB: I was thinking about endurance and compassion when I was writing this novel – and of finding the energy and faith to carry on after something so catastrophic as a war. Everything I had read in doing the research pointed to truly black things that were done during those years, sometimes by ordinary people who felt they had no option. Again and again, I was reminded that we have to remember the lessons from the past, otherwise we will repeat the wrongs. Of course, in peacetime, it is much easier to adopt straightforward moral positions. In war, and when faced with violence, deprivation and disease, it is almost impossible. Like Krista, you can still strive to feel love over hate, forgiveness over blame and compassion over brutality and still find yourself agreeing to do things which are morally questionable. EF: You write vividly on the societal changes brought about by war. Do you intend to write another novel set in this specific period or are you moving to different pastures? EB: I am not sure yet. I am still waiting for the light bulb to light up in the chest moment to find out what I am going to write about next. Mind you, I have just read a fascinating account of marriage bureau that was set up in 1939 and flourished during the war. It occurred to me that it just might have been a convincing cover for something else going on behind the scenes…. Who knows?

0 Comments

|

Subscribe to Elizabeth's quarterly newsletter below:Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed