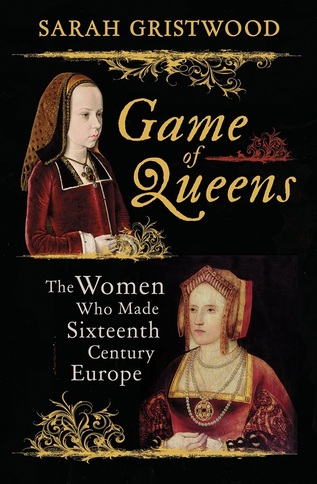

In her ambitious new book, Game of Queens, Sarah Gristwood explores the lives of twelve remarkable women, all pivotal figures in sixteenth century European politics. Through their stories Gristwood describes the complex and significant networks of female power running through Renaissance Europe that have often been overlooked by history. We are able to understand the ways in which these women were held to much higher standards than their male counterparts and draw fascinating parallels with our twenty first century female rulers, many of whom continue to face similar challenges. Gristwood casts the familiar Tudor queens such as Anne Boleyn and her daughter Elizabeth Tudor in the wider European context alongside figures like Margaret of Austria and Marguerite of Navarre, making for a rich, intriguing and impressive narrative. Here she speaks to Elizabeth Fremantle: Your previous historical biographies have focused on English women and Game of Queens, through the prism of numerous European royal women, allows us to understand the wider context of those women’s lives. What was it that first inspired you to undertake such a vast project? At an impressionable age, as a teenager, I read Garrett Mattingly’s classic book, The Defeat of the Spanish Armada, and noted his passing comment that it was sixty years since the parties of religion first squared up, the old versus the new, ‘and always by some trick of Fate one party or the other, and usually both, had been rallied and led by a woman’. When I started looking into that, I was struck by how many of these women were connected – how power and the lessons in how to wield it passed from mother to daughter, mentor to protégé. That lead me inevitably to the women of Europe, rather than just the British Isles – and then I realised that this was in a sense the real story. That there was a real international sisterhood of powerful women, which our very Anglo-centric history has rather forgotten today. I found Margaret of Austria staggeringly impressive in the way she managed to hold onto power, often against the odds. Of all the women you have written about in Game of Queensdo you have a favourite? Yes – and it’s Margaret! I totally agree. Margaret of Austria isn’t necessarily the character who occupies the largest place in our imaginations. It’s Elizabeth I and her mother Anne Boleyn at whom every Tudor historian wants a crack, but if you had to be stranded on a desert island with one of these women you’d choose Margaret, definitely. And the fact that she became in her own words, ‘the most important person in Christendom, since she acts as mediator in almost all the negotiations between the princes’ makes her the closest to a career woman of today. Some might argue that these women were only able to rule with the backing of their male relatives. I believe Game of Queens debunks this notion but can you give us a few of your thoughts about the limitations placed on renaissance women in power. It’s an interesting question – because of course it’s true; even Margaret of Austria was ruling the Netherlands on behalf of her nephew Charles V. But – big but – she took that surrogate authority and really made something of it. One question the book raised for me was about the different aspects of power – how much difference there was (or was not) between a queen regnant, ruling in her own name, and a woman who took a more traditionally feminine path to authority. We are seeing now an interesting parallel with Europe in a state of flux – then it was the Reformation and now it is Brexit. Though your book must have been finished by the time of the final vote there was a good deal of speculation about the future of Europe, was this something you had in mind when writing? Not in the immediate political sense, perhaps – but I was very aware that the sixteenth century (and before) saw a kind of pan-European sensibility. That our sense of national identity has actually taken a wrong turn, when we simply envisage John Bull standing out against his enemies. Things may have felt that way after the Reformation had divided Europe – but not before it, necessarily. Another parallel is the increase of women holding high political office but it is clear that women, even now, are held to higher standards than men when holding public office. How did the early modern torchbearers of Game of Queens negotiate this? The modern parallels are something of which I was aware – acutely! And you’re right – women are and were considered more accountable, blamed more easily, than men. They have to do everything right, to get even to the starting block, basically. At the very beginning of the period of which I’m writing Anne de Beaujeu, who’d ruled France on behalf of her teenage brother, wrote a manual of instruction for powerful women – Lessons for My Daughter. And one of her instructions was ‘guard against being deceived . . . because you can be blamed even for something very slight’. Not all the women managed to avoid this trap – just think of Anne Boleyn! But they were all aware that (as Catherine de Medici once told Elizabeth I) it was through her sexuality that a powerful woman could be attacked most easily. Though maybe that is something that has changed today . . . When working on a project of such vast scope there must be a good deal of material that has to be left out. Are there any favourite stories or anecdotes that came up in your research that ended up on the cutting room floor? It’s not so much stories, as whole personalities! Luckily, there are websites which focus on powerful women from a wider global perspective than I was able to do. I was sorry not to be able to include the Indian ranee who rode into battle on her own war elephant. But I was even more sorry not to be able to include some of the Italian women of our era, who were likewise outside the scope of this story. Women like Caterina Sforza, whom Machiavelli encountered when sent on an embassy. He described how, besieged and with her children taken hostage, Caterina pulled up her skirts and showed the besiegers ‘her genital parts’, telling them she had the means to make more children if necessary. Can you tell us a little bit about your research and writing process – for example do you have particular routines? I’m wondering too whether this book was more of a challenge to research as many of the archives must have been in other languages. Well, this book was a one-off . . . a subject so broad I suspect no academic historian would ever have tackled it. With sixteen protagonists, five countries and a century of history to cover, this was less about original archival research than other books I’ve done, and more about spotting connections between the women. What’s next for you? I haven’t had time yet even to talk to a publisher – but there is a project I’m enormously keen to do. And I can say that it’s once again about women and power – just a bit more recent than the sixteenth century! This interview was first published in Historia Magazine Game of Queens: The Women who Made Sixteenth Century Europe is out now. Find out more about Sarah Gristwood. Elizabeth Fremantle’s latest novel The Girl in the Glass Tower is published by Penguin.

1 Comment

11/18/2022 12:54:15 am

Home care outside their.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Subscribe to Elizabeth's quarterly newsletter below:Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed