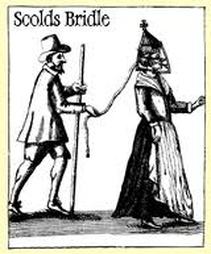

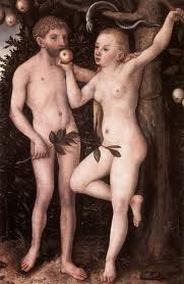

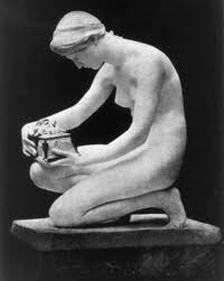

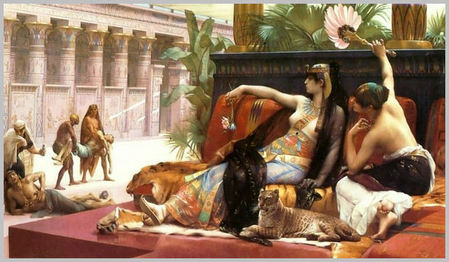

In the wake of a week that saw campaigner Caroline Criado Perez, MP Stella Creasy and classicist Mary Beard deluged with monstrous rape and death threats on social media sites it seems like an apt moment to take a look at the way women and their bodies have been portrayed historically. The true source of misogyny remains lost in the past and is certainly not limited to the Western world but I must begin somewhere, and in 750-650 BC with Hesiod and the Pandora myth seems as good a place as any. Hesiod described Pandora as 'kalon kakon' – the beautiful evil – and 'From her comes all the race of womankind/the deadly female race and tribes of wives/who live with mortal men and bring them harm.' Her story is one of temptation – her inability to resist opening the vessel (I hesitate to call it a 'box' for obvious reasons) containing all the woes of the world and dooming humanity to hardship, sickness and death. A familiar story indeed; Pandora is of course a precursor of Eve. A vessel substituted with an apple, a serpent and an angry God in the background, and we have a Judeo-Christian incarnation of the same myth. Interestingly, imagery of both Eve and Pandora tends to glorify of the naked female form, so becoming at once the symbol of sin and yet the focus of the erotic gaze. Thus women become the site of temptation itself making it impossible to separate 'beauty' from 'evil'. Pandora in the above image is, though conveniently naked, entirely absorbed in the object of her own temptation, seeming unaware of her sexual allure. (indeed, let's not forget that it was the male body that was idealised in this period.) Yet this image of Eve, by Cranach, is astonishing in its overt eroticism, particularly given this kind of image was typically displayed in a devotional context. She stands with one arm flung up, a leg flirtatiously lifted; poor Adam doesn't stand a chance and that is the point. It is no wonder men were suspicious of women – they were dictated to by a supremely powerful cultural and religious media that asked them to look at the tantalising naked form and then told them they were damned for being aroused by what they saw. By the medieval period the trope of the sexually rapacious woman whose appetites needed curbing was the norm. Unwed girls were deemed a danger to themselves and needed the marriage bed for their well-being and widows, the only women allowed a modicum of jurisdiction in society, were the butt of derisive humour that hid a deep misogynystic suspicion. Chaucer's Wife of Bath is a good example of a dangerously sexual older woman, several times widowed, irrepressibly manipulative, overly talkative and bawdy, who, despite many feminist interpretations to the contrary, is treated as a figure of ridicule. Given readers were largely male I suspect she is to be laughed at, rather than with. Medieval women had few choices and were ideally expected to be the human embodiment of the Holy Virgin – chaste, silent, biddable, pure – and yet inhabited bodies that were the site of temptation. In imagery of the Holy Virgin we see her as 'mother' in which her breasts rather than being erotic, become symbolic of nurture . The sole function of women was to be mothers, and so an uneasy alliance arose between the necessarily bodily function of birth and breast-feeding and the denial of the woman's body altogether. Looking at images of the Holy Virgin we see her either as the mother figure or as the Queen of Heaven, in which she takes her place beneath God and Jesus, serving as a blue-print for the ideal family in which women were subject to their fathers, husbands, brothers and sons. But as long as women were covered, contained, accepted their place beneath men and did not rail against laws such as those that allowed husbands to beat their wives, though not so far as to cause their death, and moreover remained silent, men and women could live alongside one another in relative harmony. These kind of restrictions on women played into the prevailing notions of woman as scheming and untrustworthy, as in order to be heard or to have an effect on their world women were dependent on manipulating the men through whom their agency was necessarily mediated. Problematically, in the second half of the sixteenth century England had no male heirs to inherit the throne, resulting in a crises for the patriarchal system. Mary I took the throne and nearly created her own downfall by choosing to marry a Spanish prince. The prevailing anxiety was that, given women and their possessions (in Mary's case that meant England) became the property of their husbands on marriage, England would become an annex of Spain. Her sister succeeded her as Elizabeth I, who famously refused to marry. She was canny enough to subvert the image of the Virgin as Queen of Heaven transforming herself into a quasi-religious virginal icon for the purposes of her public image. Yet this was at great personal sacrifice and denied her the possibility of motherhood which was essential to the continuation of the Tudor line. Also by remaining unwed, she trod a dangerous path in terms of her international reputation, being deemed a 'whore' throughout most of Catholic Europe. Ultimately she survived but, having no heir of her body, was a failure in terms of dynastic ambition. See how the two female queens are depicted below as entirely desexualised – almost like dolls or effigies and certainly not holding any dangerously erotic allure. During the reigns of the two Tudor queens, Mary and Elizabeth, there was an outpouring of misogyny that could be seen as parallel to the one we are seeing now and was a backlash against the idea of women in power. Throughout the medieval period women had, by and large, kept their heads down, with perhaps the exception of Joan of Arc and look what happened to her, but the particular coincidence of birth and death in the mid-sixteenth century that meant there were only girls in the Tudor succession proved difficult for a society with limited female paradigms to fall back on. John Knox, voiced the general unease about the dearth of male heirs with an attack on women in a 1558 pamphlet: 'The First Blast Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women.' The title needs no explanation. As Elizabeth aged and people began to look beyond her reign, she interestingly is described as wearing increasingly revealing outfits. Was this perhaps a response to the diminishment of power felt by and ageing monarch with no heir? By the time the Stuarts were on the throne women were firmly back in their boxes and society saw a sharp rise in the persecution of so-called witches and an increase in the practice of shaming women who stepped out of line with contraptions like scolds' bridles (see the above image) which were used to publically humiliate and punish wives who were not sufficiently silent. Interestingly, once women are no longer in positions of power, we begin to see them depicted in an increasingly erotic manner. Images of Anne of Denmark, James I's queen, show her with her breasts on display, echoing the depiction of the Virgin Mother, and by the end of the seventeenth century in a post-civil war world, images of women, and particularly Royal mistresses, by artists like Lely stripped back their clothing further, associating them once more with the figure of Eve. See the image below of the Duchess of Norfolk – all that is missing is the serpent. Once this striptease began it became an unstoppable force with Royal mistresses depicted in increasingly tantalising ways. The image below of Nell Gwynne unashamedly references the Virgin mother in a way that is undeniably erotic (notice how the infant in the image is trying to peek beneath the fabric covering her sexual organs) thereby conflating role of woman as mother with the dark 'other' role of whore. By the Victorian period women were literally forced back into submission by restrictive clothing and social mores and were desexualised by models of ideal female womanhood like 'the angel in the house'. If the image of the Virgin had been corrupted then what was less sexually threatening than an angel? (That angels are supposed to be male is a whole other discussion.) Whilst wives and daughters were literally shaped into the asexual ideal, images of the exotic 'other' like Cleopatra provided an arms' length sexual female figure for men to look at and be aroused. With the advent of the twentieth century and the beginnings of cinema these figures became polarised into the vamp and the girl-next-door, two visions of womanhood that persisted for decades and as long as women had no real power and no voice these didn't threaten the status quo. Men could marry the latter and desire the former unproblematically and women knew exactly where they were. Interestingly, when a woman with true power took the reigns of England in the shape of Margaret Thatcher, we see her styling herself in a manner that is desexualised echoing the earlier queens Elizabeth and Mary. The pussycat bow tied tightly to the throat, the tailored suits, the helmet of hair, denying any possibility of the typical feminine notion of softness and powerlessness – indeed the moniker 'Iron Lady' describes this perfectly. This is a woman who means business. Which brings us to women now. It is significant that the recent attacks on women focus on their physical bodies with threats of rape and dismemberment. The insults are cited in the eroticised body. How is it possible for women to both inhabit their bodies and not be damned for the way they look, when Caroline Criado Perez receives comments about a photograph of her illustrating an article about Twitter abuse, objecting to her 'prominent pair of breasts pushing themselves outwards in the direction of the reader,' suggesting that she should deny her body altogether in order to be taken seriously? I wish there was a straightforward answer but at the very least we must applaud those who resist the casting of women and their bodies as corrupting objects of temptation.

2 Comments

8/4/2013 11:40:38 pm

This is very interesting, particularly the way you use powerful women's image to explore misogyny. I've come at it from a slightly different angle, if you'd like to read it: http://jbailey2013.wordpress.com/2013/07/27/on-the-history-of-misogyny/

Reply

8/4/2013 11:55:11 pm

Thanks so much for directing me to your fascinating piece. The research of a proper historian leaves me blushing with shame! I'm so glad to see a more widespread discussion about all this emerging.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Subscribe to Elizabeth's quarterly newsletter below:Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed